How Engineering Shortcuts Turned Deadly

Why This 1970s Case Still Matters to Engineers Today

The Ford Pinto remains one of the most compelling case studies in engineering ethics, not just for its flawed fuel tank design, but for what it reveals about the complex balance between technical constraints, corporate decision-making, and ethical responsibility. The case highlights how business pressures and cost-cutting measures can lead to unintended safety risks, raising questions that continue to shape engineering practices today.

Nearly five decades later, the Pinto serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of prioritizing efficiency over safety. It challenges engineers, business leaders, and policymakers to consider how ethical frameworks should guide technological advancements.

Last year, we explored this case in a post on our Instagram page, offering key insights into its ethical dilemmas. You can check it out below. We hope you find value in this deeper dive!

A post shared by Engineering Community ???? (@engineeringcommunity_)

Engineering Under Pressure

In 1968, Ford faced mounting competition from imported subcompacts like the Volkswagen Beetle. To respond swiftly, the company set an ambitious goal: develop the Pinto in just 25 months, half the industry standard. While this aggressive timeline allowed Ford to enter the market quickly, engineering ethics researchers have since identified it as a critical factor in the safety compromises that followed.

This accelerated development came with rigid constraints:

- Weight limit: 2,000 pounds

- Cost ceiling: $2,000 (≈$17,000 in 2024 dollars)

- Market pressure: Beat foreign rivals

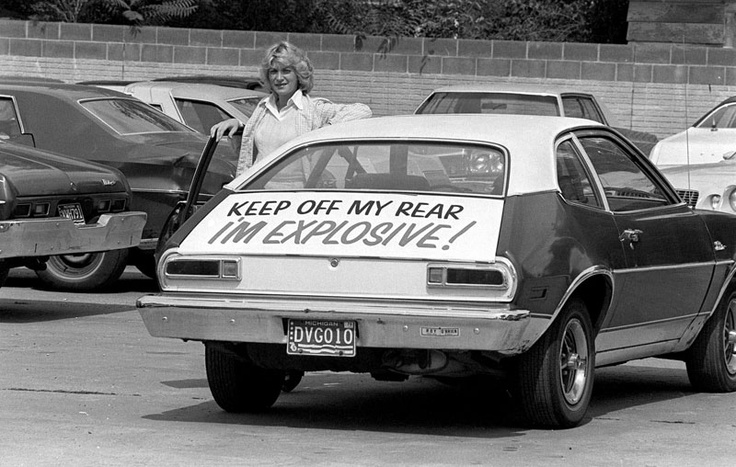

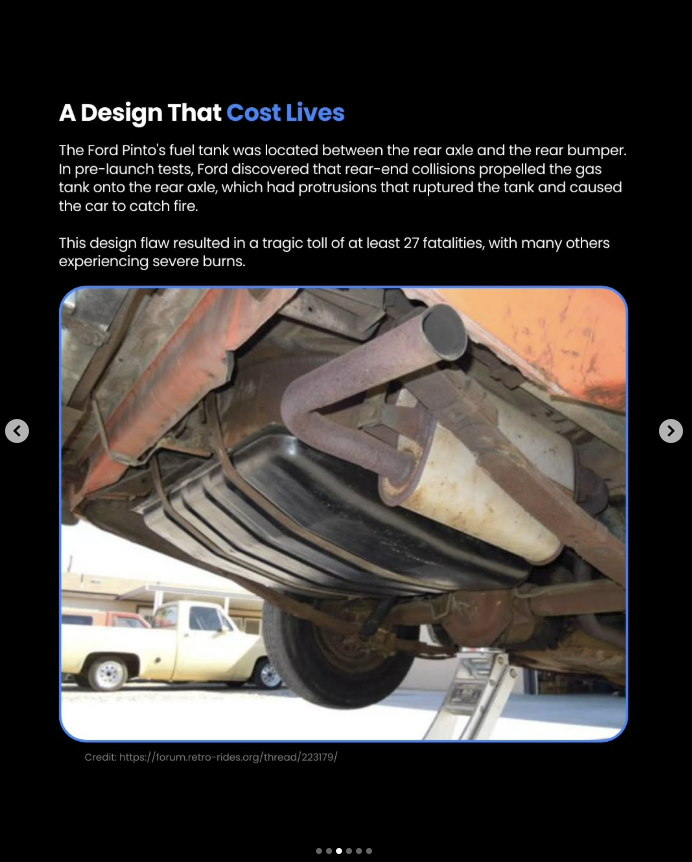

To create more trunk space, Ford engineers positioned the fuel tank behind the rear axle, an approach that was widely used at the time but carried safety risks. Later crash tests showed that in low-speed rear-end collisions, the tank could be punctured by bolts from the differential housing, leading to fuel leaks and an increased risk of fire. This design decision, driven by space and cost constraints, became one of the Pinto’s most notorious flaws.

The Ethical Dilemma Behind the Design’s design decision showcases how engineering compromises can have unintended but severe consequences.

The Fatal Flaw

While placing the fuel tank behind the rear axle was a common industry practice, it became a critical flaw in the Pinto’s design. Impact tests showed that at relatively low speeds, structural elements near the tank, specifically bolts from the differential housing, could puncture it upon collision. With fuel leaking dangerously close to ignition sources, even minor rear-end crashes had the potential to turn catastrophic.

Ford engineers weren’t oblivious to these risks. They proposed several solutions, including:

- A plastic baffle costing approximately $1 per vehicle

- Repositioning the tank above the axle

- Adding reinforcement to prevent tank puncture

However, as court documents later revealed, management rejected these proposals, primarily to avoid production delays and additional costs, a decision that would have profound implications for public safety and corporate liability.

The Infamous “Pinto Memo”: Data Misused or Misunderstood?

Perhaps no document better encapsulates the ethical controversy than the so-called “Pinto Memo” (officially titled “Fatalities Associated With Crash-Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires”). This internal cost-benefit analysis weighed the financial cost of safety improvements against potential litigation expenses, leading to one of the most controversial decisions in automotive history.

Ford’s Cost-Benefit Breakdown

| Expense Category | Formula | Calculated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Improvement Costs | $11 per vehicle × 12.5 million vehicles | $137 million |

| Estimated Lawsuit Costs | ||

| – Deaths | 180 deaths × $200,000 per death | $36 million |

| – Injuries | 180 injuries × $67,000 per injury | $12.1 million |

| – Vehicle Damage Claims | 2,100 damaged vehicles × $700 per vehicle | $1.47 million |

| Total Estimated Litigation Cost | $36M + $12.1M + $1.47M | $49.5 million |

Ford’s conclusion? The cost of implementing safety improvements ($137 million) far exceeded the projected litigation expenses ($49.5 million), leading the company to forgo the fix, a decision that would later fuel intense ethical scrutiny.

The Overlooked Context

While the memo is often cited as evidence of corporate negligence, several key points are frequently misunderstood:

- The $200,000 life valuation wasn’t Ford’s invention, it was a standardized figure from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

- The memo was part of a regulatory petition, not an internal directive to reject safety improvements.

- Cost-benefit analyses like this were common across industries in the 1970s, raising broader ethical concerns beyond Ford alone.

Despite these nuances, the memo became a symbol of corporate decision-making that appeared to prioritize profits over human lives. It remains one of the most widely discussed case studies in engineering ethics, shaping modern perspectives on corporate responsibility and regulatory oversight.

The Aftermath: Recall, Litigation, and Regulatory Change

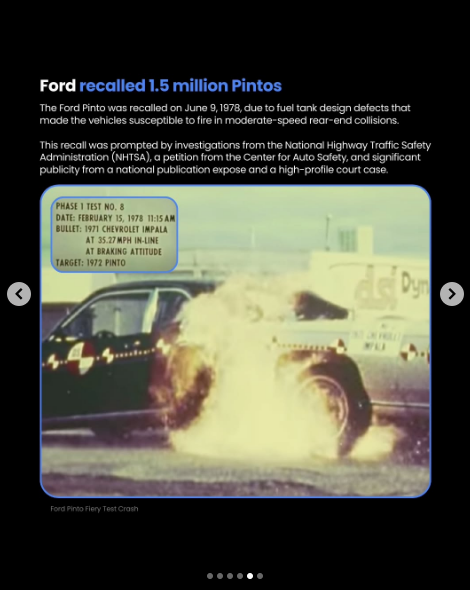

By the late 1970s, the safety concerns surrounding the Ford Pinto had escalated into a full-blown crisis. Mounting evidence of fuel system failures in rear-end collisions forced Ford to take action:

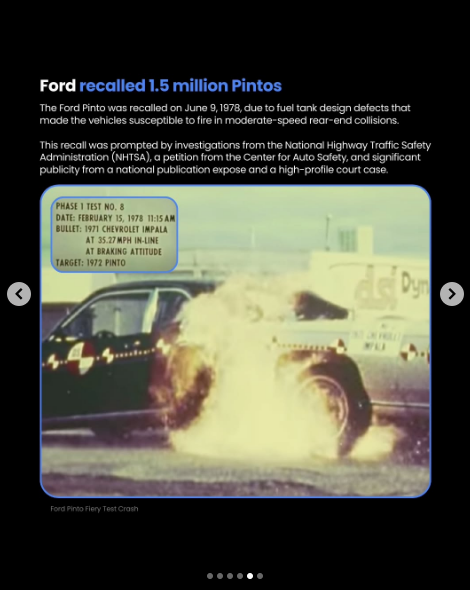

- Mass Recall: In 1978, Ford recalled 1.5 million Pintos and Mercury Bobcats to modify their fuel systems, marking one of the largest safety recalls in automotive history.

- Landmark Lawsuit: The Grimshaw v. Ford Motor Co. case resulted in a $125 million punitive damages award, later reduced to $3.5 million. This was one of the largest product liability verdicts at the time, setting a precedent for corporate accountability in safety-related lawsuits.

- Regulatory Overhaul: The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) responded by implementing stricter fuel system integrity standards (FMVSS 301), fundamentally reshaping automotive safety regulations.

Fatalities and the True Human Cost

While official estimates vary, NHTSA data linked 27 fatalities to Pinto fires between 1971 and 1977. However, independent investigations suggest the actual number may have been much higher, with some estimates ranging between 500 and 900 deaths.

The Pinto case also highlighted broader concerns about corporate decision-making in safety-critical industries. The regulatory aftermath led to the development of new crash-testing procedures, influencing how automakers design fuel systems to this day.

Separating Myth from Reality

The Pinto case has accumulated its share of misconceptions over the years:

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| “Ford valued profits over lives.” | The $200,000 life valuation came from NHTSA, not Ford. |

| “Pintos were unique deathtraps.” | Fatality rates were comparable to peers; the AMC Gremlin and Chevrolet Vega had similar fuel tank vulnerabilities. |

| “Engineers ignored the problem.” | Engineers proposed solutions, but corporate priorities delayed implementation. |

| “All Pintos exploded in rear-end collisions.” | The failure mode occurred primarily in a specific speed range (20-25 mph) under certain impact conditions. |

Engineering Ethics Lessons for Today’s STEM Professionals

1. Systems Thinking is Essential

The Pinto’s fuel tank wasn’t merely a component issue but a systems failure, as detailed in engineering safety analyses. When designing critical systems, engineers must:

- Consider interactions between components under various conditions

- Evaluate potential failure modes across the entire system

- Assess how manufacturing tolerances might affect safety margins

2. Data Doesn’t Replace Moral Judgment

While cost-benefit analyses are valuable tools, they cannot substitute for ethical reasoning:

- Quantitative models cannot fully capture all values at stake

- Human lives and well-being must never be reduced to mere financial calculations

- Long-term costs of reputation damage and public trust aren’t easily quantified

3. Psychological Safety Enables Ethical Engineering

Organizations must create environments where engineers can raise concerns without fear:

- Clear reporting mechanisms for safety issues

- Protection for those who identify potential problems

- Recognition for identifying risks, not just meeting deadlines

4. Regulation Has a Role in Driving Innovation

The Pinto case demonstrates how regulation can actually spur innovation, as evidenced by subsequent safety improvements:

- Post-Pinto NHTSA standards led to safer fuel system designs industry-wide

- Regulatory frameworks establish minimum safety standards when market forces might not

- Modern parallels exist in AI ethics frameworks and autonomous vehicle safety standards

The Pinto’s Legacy in Today’s Tech Challenges

The ethical dilemmas faced by Ford engineers in the 1970s continue to resurface in different contexts, with striking similarities:

- Boeing’s 737 MAX development faced similar time and cost pressures

- Self-driving car manufacturers must decide how to balance innovation with safety testing

- Medical device companies weigh bringing life-saving technology to market quickly versus extensive safety validation

The Enduring Relevance of the Pinto Case

The Ford Pinto story isn’t just a cautionary tale, it’s a blueprint for understanding the ethical challenges that engineers, designers, and decision-makers face every day. It reminds us that technical choices are rarely made in isolation; they unfold within a web of corporate deadlines, financial constraints, and societal expectations.

By reflecting on failures like the Pinto, we can shape a future where engineering integrity is prioritized, where ethical compromises are caught before they become tragedies, and where innovation never comes at the cost of human lives. The progress we see today in vehicle safety, from advanced crash testing to reinforced fuel systems, is proof that lessons learned decades ago continue to save lives.

Share Your Thoughts!

What engineering ethics case studies have shaped your professional approach? Join the conversation and let us know your thoughts over on our Instagram at Engineering Community!